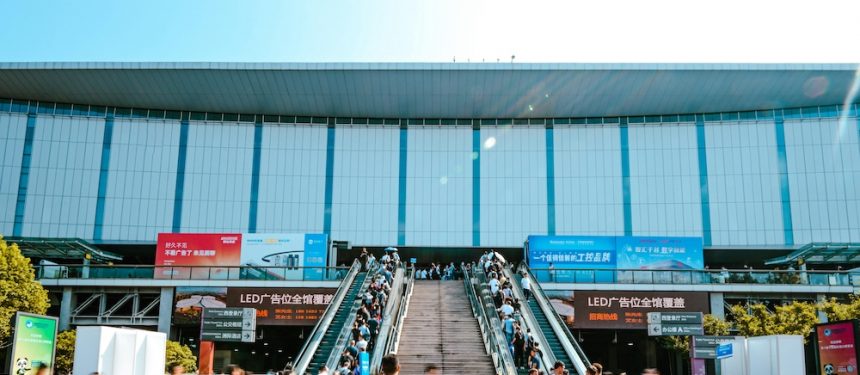

During the recent China Study Abroad forum, it was announced that multiple institutions had signed MoUs with Australia and Canadian universities, with the aim of “deepening educational connections” between the countries.

Speaking to The PIE, Phil Honeywood, chief executive of IEAA, said the MoUs – as well as the document signed in late March between Australia and China’s governments – are a “welcome sign of return to normalcy”.

“There is no doubt that, since the election of the Albanese government in 2022, the relationship [in general] has significantly improved.

“However, the overall number of students from China studying in Australia remains well below pre-Covid figures,” he warned.

Honeywood noted that many nuances still exist in the international student bilateral relationship, including very little “co-ordination and incentive for Australian secondary schools to deliver curricula into China”.

“In contrast, the UK, US and China have presided over massive growth in the number of international high schools teaching their university pathway programs [there],” Honeywood explained.

Canada’s relationship timeline has been a similar one with China. Before the pandemic, the arrest of a Huawei executive in Vancouver dented the bilateral correspondence landscape.

“We’ve had to dig ourselves out of a big hole in/with China to get back to where we are now,” Randall Martin, executive director at the British Columbia Council of International Education, told The PIE.

But he said that the relationship thaw since the pandemic “continues apace”, with more senior levels of engagement and good will “being expressed by both sides” in the international education space.

“The [forum] was an appropriate [time] to go back to China to renew MOUs with two major national associations – CEAIE and CSCSE – which function as platforms for institutional success in partnerships and to a degree in recruitment for BC K-12 districts and post-secondary institutions.

“I think institutional and jurisdictional relationships have matured between the two countries, and we are increasingly at a place where we can respect differences and speak of issues openly,” Martin posited.

This is a stark difference to the issues faced by the UK and US in terms of their institutional relationships with China.

In the UK, prime minister Rishi Sunak has flip-flopped on whether he would close the country’s Confucius Institutes, and the first education mission to China since before Covid only took place in October.

Multiple instances in reports and in committee hearings in the House of Commons have also showcased the geopolitical tension which has strained the UK relationship.

In the US, tensions have long been growing, despite China’s continued interest in the country as a study destination. In the last six months, multiple bills have also been introduced – chiefly by Republicans – to try and “curb foreign interference” in higher education.

Despite more recent efforts to get more students studying abroad in China from the US, delivering on president Xi Jinping’s goals, the tensions have continued to be prevalent in multiple industries – secretary of state Antony Blinken visited Shanghai on April 24 to try and maintain an open dialogue, despite issuing warnings to China on multiple fronts.

Martin noted multiple parents he recently spoke to said the appetite for study in Canada was “still strong”.

“[This is] especially with a concern I heard voiced daily: the increased parental concern for their children’s safety in at least one other English-speaking destination,” he said.

“I think institutional and jurisdictional relationships have matured between [China and Canada]”

Canada featured heavily at the CSAF, with the country “prominently represented at the opening plenary” and throughout.

Tim Hubbard, head of east Asia recruitment partnerships at UK-based UEA, told The PIE that he still left the forum with the impression the UK “remains the most popular choice” for international partnership.

“Universities from Australia, Canada, Singapore and other countries also participated in the events and are becoming more interested in developing partnerships with Chinese universities,” he noted, characterising the interests as if they were in more of a fledgling stage.

“Many Australian universities have scored well in the recent QS World Rankings – which are extremely important in China – and should they develop strong partnerships then they are likely to be very attractive options to students,” Hubbard added.

Honeywood, while positive about the recovery of Australia’s China relationship, noted that the UK and US are “greater beneficiaries” of the Golden Ticket initiative in China, even with increasing numbers of Australian universities in play – and Chinese parent perceptions remain a barrier.

“There is anecdotal evidence that fears of another global pandemic have led to a ‘keep my only child close to home’ syndrome. This is seen to account for increased Chinese student enrolments in HK and Singapore institutions.

“The syndrome might also account for the one Australian state that had the longest Covid lockdowns in the world, Victoria, having not recovered its overseas student market share compared to all other states,” he added.