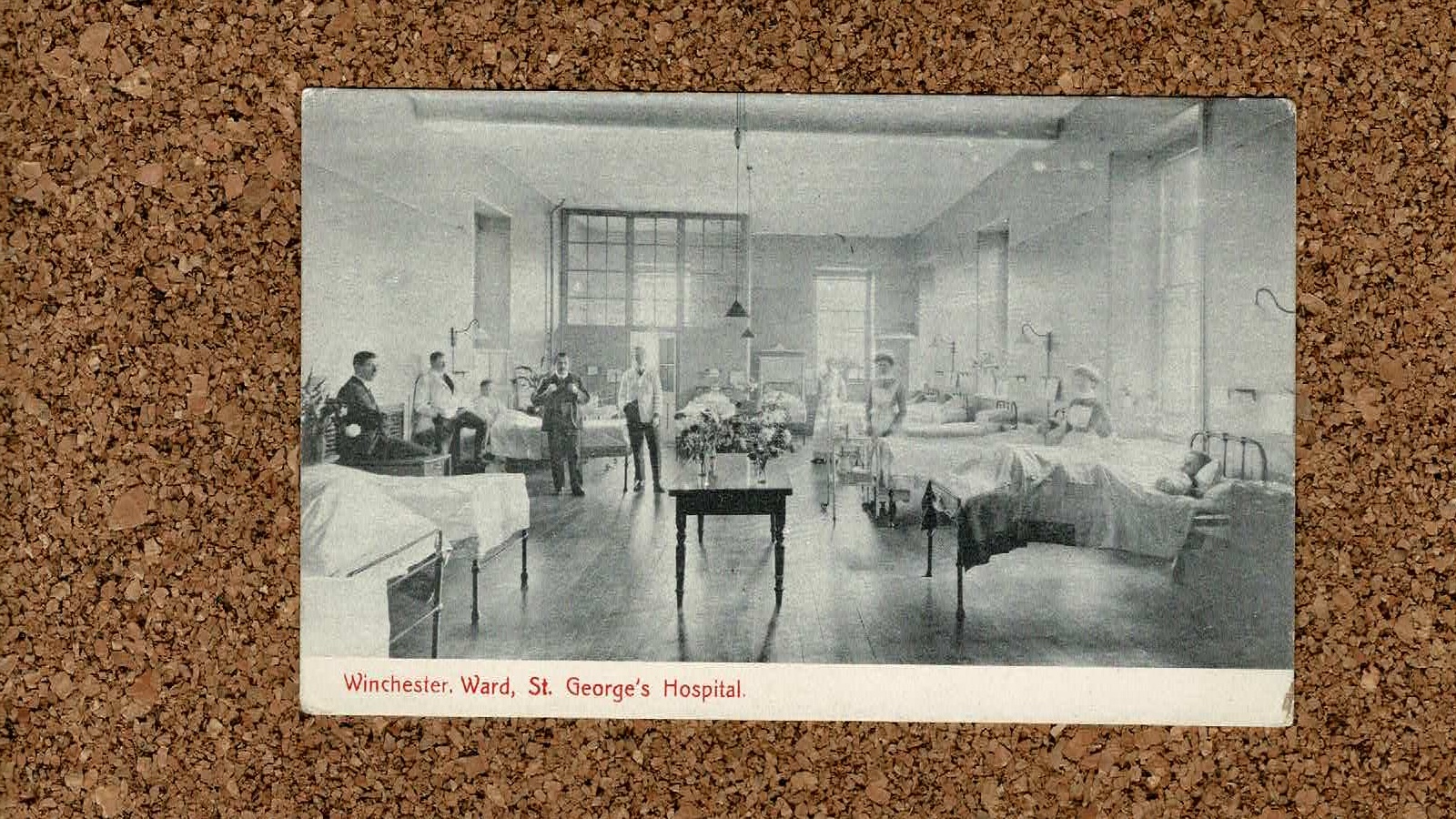

If you’re observant, you may have noticed that today’s card appears to show a hospital ward, and not a seat of learning. Read on, and find out why the two can be one and the same!

It’s 1752. If you want to be a doctor in England, training is a practical matter: you follow established doctors and surgeons in their hospital practice, learning on the job, as it were. There was a professional body – the College of Physicians, established in 1518 – and there were some university-based educators in the underlying science (for example, Cambridge had a readership in medicine in 1524 and a chair in physic in 1540) but we are a long way from medical degrees.

St George’s Hospital, then at Hyde Park Corner in London, started to keep a register of pupils who were attached to the physicians and surgeons in the hospital. Early figures associated with the hospital include John Hunter (pioneering surgeon, in whose honour the Hunterian museum is named) and Edward Jenner (of vaccination fame), who studied at the hospital from 1700 to 1772. And at some point before 1803 there were lectures, given by Sir Everard Home, eminent surgeon and brother-in-law to Hunter.

St George’s, University of London dates its establishment from 1752. Note therefore that the important event was not teaching, which was taking place informally before 1752, but registering students. The registry, as any fule kno, is at the heart of the university. (Between 2004 and 2007 I was Academic Registrar at St George’s and I can attest that this statement is true.)

The next date we need to know about is 1834. The hospital had been rebuilt, and one of its surgeons, Benjamin Brodie, bought a house on nearby Kinnerton Street, which he leased to the hospital. The medical school is formally established. And two years later, it becomes a school of the fledgeling University of London: the St George’s Hospital Medical School.

Another notable name needs to be mentioned. Henry Gray enrolled to study medicine at St George’s in 1845, when he was 18. Seven years later he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society. He continued to work at St George’s, as anatomy demonstrator and curator of the museum, before becoming lecturer in anatomy. And he then wrote, with fellow alumnus Henry Vandyke Carter supplying the illustrations, the textbook which is now known as Gray’s Anatomy.

In 1868 the medical school moved to premises within the hospital grounds. This was good. Medical education is a combination of classroom and clinical work, and the easier it is to transition from one to the other, the better. Geography matters.

Let’s have another name. Edward Wilson graduated in natural sciences from Cambridge and, after a sojourn studying art and poetry, studied at St George’s. Before graduation he became ill with pneumonia, and spent time in Switzerland, before returning to complete his studies. And he then became Junior Surgeon and Vertebrate Zoologist on the British National Arctic Expedition, led by Captain Robert Falcon Scott, which was soon to depart. Wilson served in the “Discovery” expedition of 1901-04 and the ill-fated “Terra Nova” expedition of 1910-12, which ended with Wilson, and his comrades Scott, Bowers, Evans and Oates, perishing in the Antarctic winter, having been beaten to the south pole by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen.

In 1915 women were admitted as medical students at St George’s: four at first, apparently in response to staffing shortages caused by the first world war. They were Helen Inglby, Hetty Ethelberta Claremont, Marian M Bostock and Elizabeth O’Flynn.

Post world war two, the introduction of the National Health Service brought planning. And, in due course, two significant changes. Firstly, the move from Hyde Park Corner to Tooting, in the 1970s and 1980s, to a new large hospital building, to serve southwest London. The medical school again was integrated into the hospital building, with building names reflecting its Hyde Park Corner heritage. It’s not a glamorous site, but it’s an important and practical one.

And secondly the rationalisation of medical education in London in the 1980s and 1990s. Each hospital had had its own medical school, and these had mostly been free-standing schools of the University of London. But a process of amalgamation and merger led to the incorporation of almost all schools into other multi-faculty schools of the university:

- Guys, St Thomas’s and King’s became part of King’s College London

- the Middlesex, the Royal Free and University College Hospital became part of University College London

- the Royal London and St Bartholomew’s became part of Queen Mary and Westfield College

- St Mary’s and the Royal Postgraduate Medical School became part of Imperial College.

St George’s remained (for now) independent, and fiercely proud of it. But the financial and academic realities of small, single focus colleges were implacable: not enough money to invest in libraries, labs and so on; at risk of vicissitudes in policy and market changes; lacking the breadth for academic interdisciplinary collaboration. A number of approaches were tried; a joint faculty of health and social care sciences with Kingston University; collaboration and merger talks with Kingston and Royal Holloway. But these came to naught.

Innovation continued: a four-year, graduate entry medical degree programme was launched in 2000, now much copied elsewhere; and in 2011 a partnership with the University of Nicosia led to the first medical degree to be taught in Cyprus. And St George’s Hospital Medical School became St George’s, University of London on 23 April 2005.

And now the future lies with merger: St George’s is, subject to regulatory approvals, to merge with City, University of London, from August 2024. Before I worked at St George’s I worked at City, so know both institutions well. And I think it is a good plan: the provision at both will benefit, and Angel to Tooting Broadway, or vice versa, is as good as any tube journey on the northern line. The new institution is to be called City St George’s, University of London. Long may it thrive!

The card itself was sent on February 20 1908 to Miss Alexandre, in West Linton, Peebleshire, which is a few miles south west of Edinburgh. The sender was clearly a medical student.

Result of exams just out – have come out well. Had 2 exams to-day and enjoyed them immensely. Glad to get your PC [postcard] and to hear our dear one is getting on so well. I hope to write to Millie for Saturday mail a long letter now that this worry is all over. Lots of love, ever yours, [illegible]