When Bridget Phillipson has been reminding journalists and fringe attendees that the 2023 onwards UG loan system in England is “regressive”, you do wonder who that’s been aimed at.

On LBC on the eve of Labour Party conference, for example, the Secretary of State said:

I think that’s a really unpalatable choice, not least given the very difficult funding system that we have overall. So the system that came in as of last year has become even more regressive, less progressive, less fair, shall we say.

“Is it off the table entirely?”

“It’s not something I would want to go to, but…”

@Lewis_Goodall puts Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson on the spot over the potential increase of tuition fees for university students. pic.twitter.com/HSmxaJDhgc— LBC (@LBC) September 22, 2024

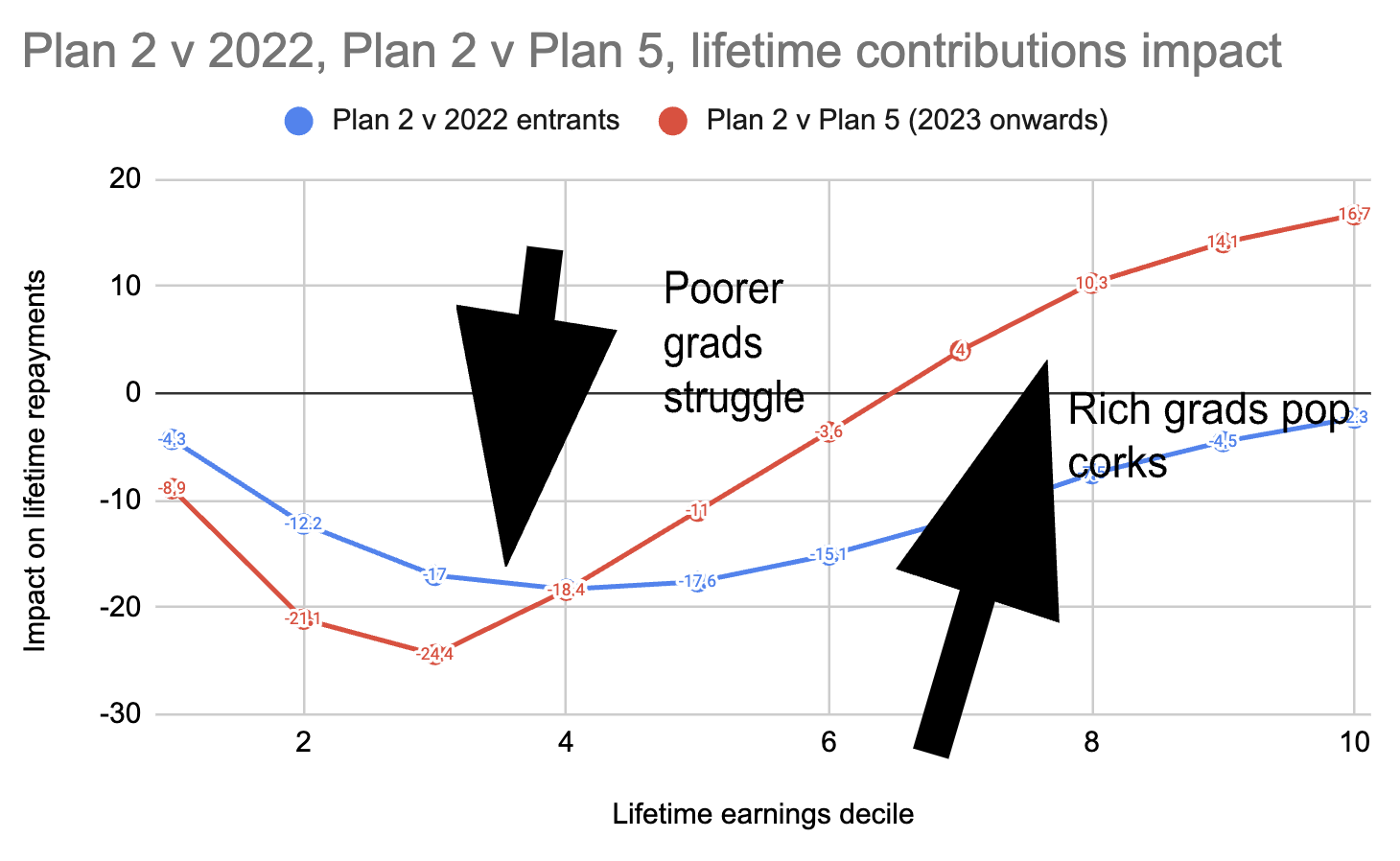

There surely can’t be more than about 50 people in the country who clock that she’s basically talking about this graph, which explains which earners (over their lifetime) became better off, or worse off, under a) the 2022 tweaks or b) Plan 5 (2023 onwards):

Of course the other thing that’s been happening at the event is speculation about Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ budget, and the changes she might make to the government’s (self-imposed as a way to not spook the markets, Truss-style) fiscal rules to give her some headroom to invest.

We might therefore assume that one of the conversations that’s been going on behind the scenes is a clear signal from No.11 that there’s no more money, but at least an in-principle conversation about how a theoretical similar-sized envelope might be better spent in HE in the short term.

If nothing else, skills minister Jacqui Smith will have to announce 2025’s tuition fees and maintenance loan rates for England fairly soon – and given the signals both she and Bridget Phillipson have been sending about having “heard” calls for relief from both universities and students, it would be odd if the status quo was rolled out again.

As such, HEPI has an interesting paper out from economist Tim Leunig that resonates with work our own Mark Leach was brandishing about at 2023’s Labour Party Conference – it takes the same theoretical long-term envelope of funding per cohort, and has a run at spending it better.

Leunig’s package provides some relief to universities and students in the form of extra teaching funding and a better maintenance package – which includes some grant alongside the loan. It’s where Leunig thinks it should be raised from that gets interesting. And while it has been trailed as a “bombshell paper”, it’s almost certainly not radical enough.

What a relief for everyone

On the relief side, the headline for finance directors is a proposal of a £2,000 increase to the unit of resource – grant funding rather than an increase in fees. Don’t get too excited – Leunig hedges his bets on whether that should just be doled out per head, differentiated by subject or differentiated by costs. Fair enough – that’s a whole other paper in and of itself.

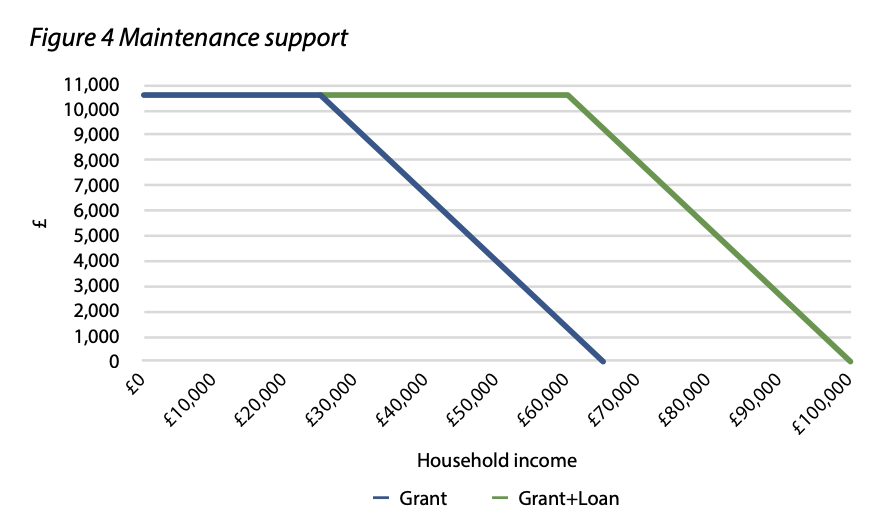

On the maintenance side, there’s then a fairly complicated set of proposals with a means-test taper – a mixture of grant and loan designed to reduce the “poorest students graduate with the biggest debts” problem:

The big problem with the proposal is that even with parental contribution, it only comes to £10,600 (away from home, outside of London) – some distance from Augar and Wales’ anchor to the minimum wage, and even further from HEPI’s own minimum income for students work.

- Low Pay Commission April 2025 minimum wage prediction: £11.89 per hour

- x 37.5 hours per week, 30 weeks per year: £13,376

- Augar/Wales v Leunig shortfall: £2,776

- HEPI minimum income for students: £18,632

- HEPI minimum income standard v HEPI Leunig shortfall: £8,032

And like pretty much everyone since the three rates were invented, Leunig doesn’t interrogate whether the lower rates for students at home or the higher rates for students in London are right – he just applies the percentages that we’ve been applying for three decades.

It’s actually a bit worse than I’ve implied – partly because later in the paper, Leunig reckons that universities can be relieved of the need to fund student financial support in their access and participation plans as a result of his extra cash for students.

OfS figures put the value of that in 2022-23 at £3,526 for those helped – so students entitled to any of that would be much worse off.

Recovery rates

Once you’ve splashed the cash, you need some of its back – and you have choices.

There’s how long you spend getting it back in – the longer you stretch it out over, the more uncertain the figures get and the nervier the Treasury is.

Then, over that period, there’s who you take it from, and when you take it from them. Have a low repayment threshold and you soak young graduates. Have high interest rates and you take it mainly from rich men in their fifties, and so on.

Leunig has a suite of twiddles in this space – none of which are especially easy to cost on their own because of compound impacts – but they run largely like this:

- Take the current loan term and reduce it from 40 to 20 years – because being in debt feels bad

- Jack up repayment rates by an additional 3 per cent of income between the income tax and student loan repayment thresholds – because grads can afford it by then

- Loan interest for 2023 onwards (ie Plan 5) is RPI – he’d reintroduce an interest rate “supplement” on top of that for graduates earning over £40,000 a year, set at a maximum of 4 per cent for those earning over £60,000, again because they can afford it by then

- A new 1 per cent National Insurance surcharge for employers that recruit graduates – that would apply to all of them, whether they’d take out loans or not

And then one other killer – a minimum £10 a week (£520 a year) repayment rate regardless of whether you’re out of work, ill, or whatever.

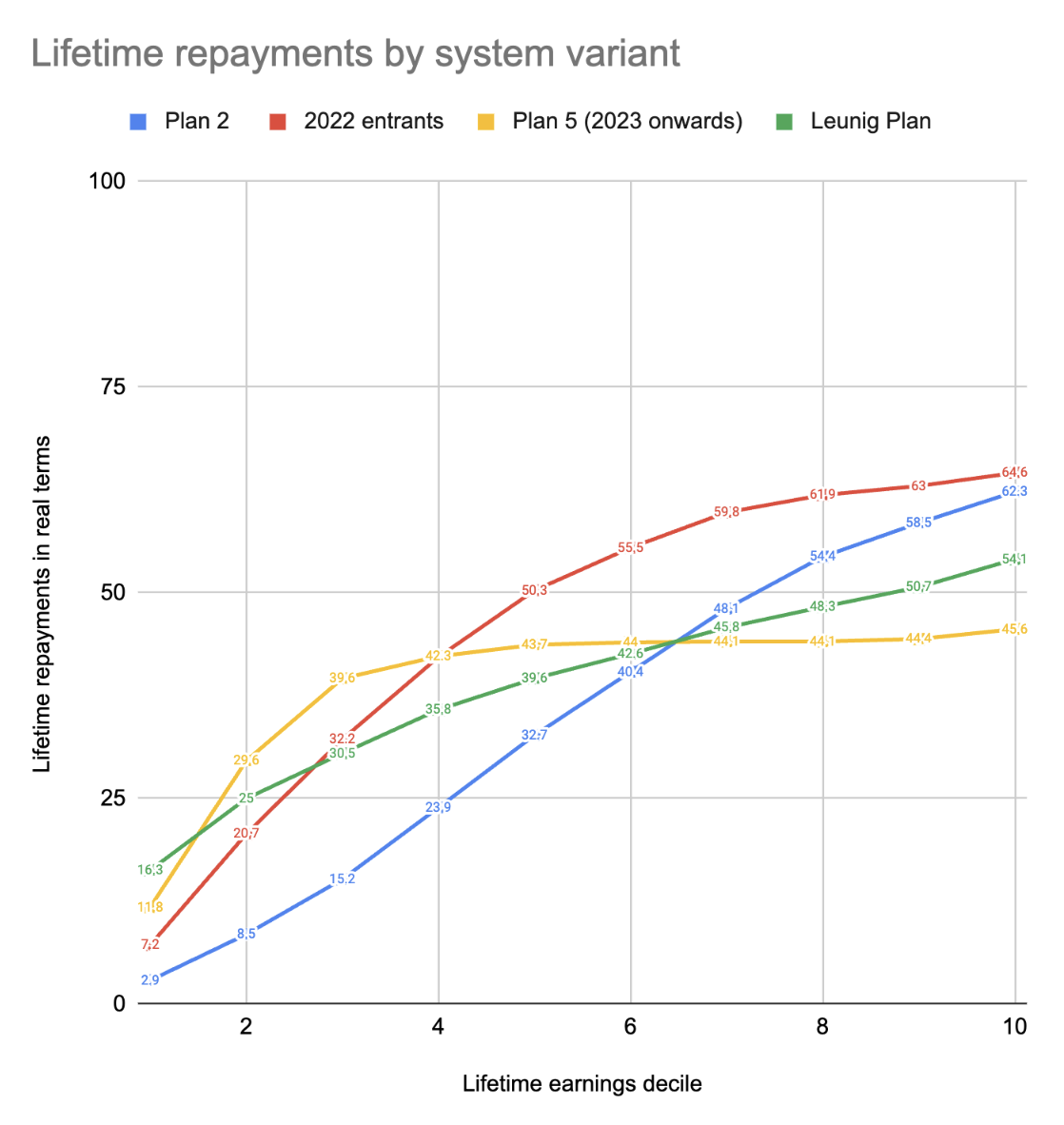

It’s a fairly confusing set of tweaks that tend to play towards the “frame it as a loan” end of the loan/tax see-saw – and the impacts would play out as follows:

If you keep your eyes on the yellow and green lines, it’s absolutely the case that the headline is that it would be more progressive than Plan 5 – lifetime earnings deciles 7 and above pay more, and most of everyone else pays less.

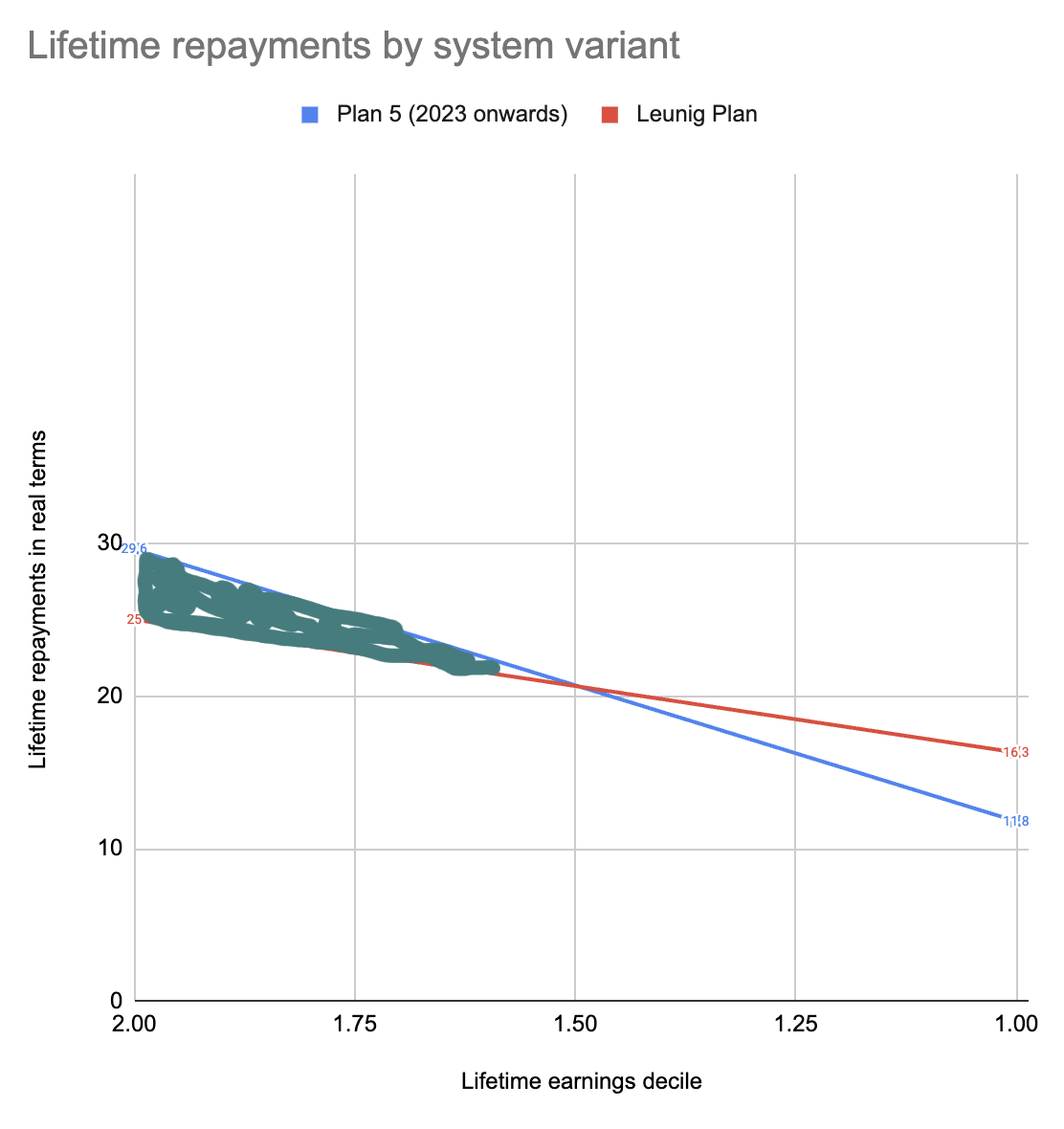

We should zoom in a bit on that £10 a week thing, mind:

In the costings model it’s worth £2.1 billion a year, but is accompanied by things like this:

For those without earnings, the payments would be made by direct debit… Society does, of course, need to be careful in how we treat those in poverty. That said, there are many circumstances that we do not correct for via the benefits system – those who need a car because they live in a rural area get no additional funding, nor do those who smoke, or have a pet. Those who have to find £10 a week because they went to university will be expected to do so come what may.

There are many things that I can imagine coming out of the mouths of Jacqui Smith or Bridget Phillipson, and that’s not one of them.

Pulling the levers

There’s a few other little bits – a proposal to stop interest being added while students are still studying, some sort of ban on 4-year degrees that doesn’t seem to have noticed foundation year students at all, and a surreal suggestion that students should be able to take out the tuition and maintenance components as a loan lump, as they do in the PG schemes.

That’s justified on the basis that universities will suddenly start competing for numbers by cutting fees – an assumption that, politely, may need a little more modelling.

Add it all up, and it’s a fairly complex set of answers to the fiscally-neutral envelope question – the complexity won’t help with the fact that nobody understands the system as it is, but it does provide a bit more resource for both universities and students by bot robbing from rich and poor graduates.

But alternatives are available. If we take Mark’s back-of-napkin scheme from last year and just put interest above RPI back on student loans – making the whole thing much more like a tax than a loan – we could notionally afford:

- An (Augar-proposed) living wage-indexed maintenance package, where everyone can borrow the maximum amount (Wales style)

- A reduction in the repayment rate above threshold for graduates to 8 per cent (from 9 per cent)

- An increase of £2,500 per student on the teaching (strategic priorities) grant

- A £500 per-student mental health fund, the use of which would be directed by students

- A rise in the repayment threshold to the median real terms salary for graduates (£26,500)

That’s a package that would also be technically fiscally neutral, and actually reduce overall graduate contributions for (the bottom) earnings half of all women from where they’re projected to be today.

A people’s trust

Naturally what the Leunig paper doesn’t do is address the myriad of other issues. The overall contribution from the state versus the graduate, what students actually need to live on, whether they should all be doing what they’re doing where they’re doing it, whether the interaction with the benefits system needs a proper look, whether the home and London rates are right – I could go on.

If (and it’s a big if) the Treasury is notionally happy with higher outlay today, we can all play with the IFS calculator to tweak the envelope – but doing so wouldn’t tackle the overall underfunding of the system, and nor does it pick up all of the other things wrong with the system – like that ramming students through at top speed thing I keep going on about.

But overall, what I’m especially struck by is the extensive commentary from Leunig in the HEPI paper on the way a debt/loan scheme is perceived – partly because even with his tweaks, there will still be a big debt and a couple of decades of repayments to contend with.

As I observe above, the alternative push on the see-saw is to see the system more as a tax than a(n ever-) growing debt.

Interest on student loans always sounds bad – but if we’d taken Plan 2 and put it up to a million per cent, the only material difference would have been that some (largely male) rich graduates in their fifties wouldn’t have been let off paying their fairly straightforward 30 year graduate tax early.

And that does take us back to a graduate tax contribution scheme. Leunig’s 1 per cent National Insurance surcharge for employers that recruit graduates is a version, and another version would be something along the lines of a 25 year tax (matching mortgages) with a much higher salary threshold, a much lower monthly repayment rate, none of this “make the bed-ridden pay a tenner a week” nonsense, and a shed-ton of cash freed up to support students and universities.

The last time a big sector funding blueprint was published, we even managed to make it hypothecated.

The Treasury use(d) loans to keep costs off the books until it was made to put them on the books again. Without much, much more public subsidy, they’re never going to work – but one where graduates take responsibility for future generations’ higher education in a way that aligns with the financial benefits they get from participation is exactly why I’d argue the People’s Trust for Higher Education is an idea that is both progressive, and one whose time has belatedly come.

As UUK’s Vivienne Stern (almost) put it on the fringe at the Labour conference:

I think there may be an opportunity to start to get the generation of people who benefited from higher education, and I include myself in that, to think about supporting universities. And I think there’s a group of people who are now becoming, you know, sufficiently, you know, have reached a point in their lives when they ought to be thinking about it, and that’s an audience we should be building support for giving back to universities amongst.