The Department for Education (DfE) has published the “second stage” report from its Higher education mental health implementation taskforce.

This, you’ll recall, was the body set up to coordinate activity emerging from previous universities minister Robert Halfon’s refusal to countenance a legal duty of care for students to apply in universities.

The good news is that there has been some steady progress in a number of areas – although we are some distance both from the original ministerial promises made, and the speed with which their implementation was originally promised.

The now Jacqui Smith authored foreword does what Labour ministers in 2024 are supposed to do – links the work to (one of the) government’s mission(s):

This government has a clear mission: to usher in a new era of opportunity. We are making a promise to our children and grandchildren: if you work hard, you’ll be able to get on, regardless of your background. We can’t do this without confronting the concerning rise of mental ill health in children and young people.

There’s even a tweet about it:

We’re working to make sure student wellbeing never goes unnoticed 💙

✅ £15m to boost uni mental health services

✅ 113 unis signed up to the Mental Health Charter

✅ 8,500 more NHS mental health staffBecause no student should face challenges alone. pic.twitter.com/6f7TTe1k90

— Jacqui Smith (@Jacqui_Smith1) December 5, 2024

…although the rolling in of the old “magic money twig”, this time used to bulk up a paltry £15m to make it sound like £281m is a bit of a cheek. I had rather hoped that that old trick had ended when the last government was swept from power.

The headline stat in the intro is that a “milestone” of 113 universities have now signed up to the University Mental Health Charter Programme. Anyone with DAPs is eligible, so that’s 49 short – but Smith is silent over whether that means Halfon’s “everyone has to do this or I’ll legislate / make OfS make it a regulatory thing” three-line whip has been carried over into the new government. More on that below.

In the Department’s intro, the question on resourcing is tackled head-on – sort of. The taskforce, we are told, is aware that many institutions are facing increasing financial challenges at present, which raises “understandable concerns” from all sides about the capacity of providers to continue to improve mental health support:

The focus of the Taskforce is on good practice; whilst on occasion this may require additional investment, in many areas discussed below it is probably no more expensive to do things well than it is to do them poorly.

I’m not especially convinced that that argument holds – or indeed would work – if you’re one of the providers having to make drastic and serious cuts, although the taskforce says it has prioritised work it believes could bring about notable improvements in student outcomes and where – through preventative activity – early action could bring about savings in the long run.

I’d tentatively suggest that if the panel believes that a coherent return-on-investment argument would work, that’s going to need some numbers and impact assessment processes putting behind it. We might also argue that now that so many providers are taking part in the UMHC, a sense from Student Minds on the distance left to travel, and any regression (either in participation or progress) towards an award ought to be shared.

Let’s all go down the strands

There were several strands to the original terms of reference. What’s called here “the adoption of common principles and baselines for approaches across providers” is the first one – and is another way of describing that three-line whip on the UMHC.

The issue there in the minutes over the months and in this report is evidently that smaller providers have complained about the complexity of the Charter and its expectations – as well as FE providers arguing that the (lighter touch) Association of Colleges charter already covers them. That’s all been handled by asking Independent HE and Guild HE to support their members who say they’re unable to join a charter programme to “adopt the principles” of the UMHC by September 2024.

There’s no news here on how many did, nor what that actually means for the gap between the expectations in the UMHC and the reality for those students in those providers.

More broadly, the update does raise real questions about progress. Student Minds published a bunch of documents last week, which if nothing else reveal a whole range of concerns about entire areas of the charter not being properly adopted, and a whole group of providers that it labels “first generation” as follows:

- Innovation and work are often ad hoc and occur within individual departments or areas.

- Mental health and wellbeing are not seen as being interconnected with coreuniversity missions or business but rather as an ‘add-on’ or additional activitymuch of the work in relation to mental health is heavily centred around student services and the provision of support, with some limited elements of proactive outreach

- There may be examples of some good initiatives in other departments, but theytend to be ad hoc, reliant on key individuals, and often siloed

- Responses across the university are often seen as inconsistent and, in some cases, contradictory

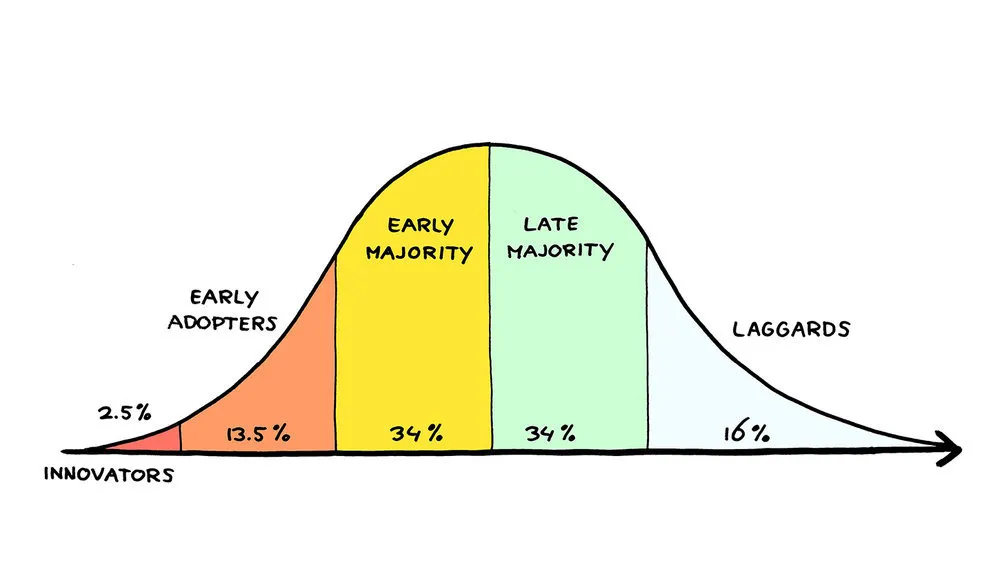

At some stage, without regulation, signing up to the UMHC (which isn’t even really an input, let alone an output or outcome) will need to morph into “how much progress is being made” – with a plan to tackle what the change consultants would call the laggards.

Enrolment, as OfS often reminds us, is neither continuation, completion nor graduate job.

There’s also a curious silence over students in franchised providers and TNE that someone will need to notice at some stage. Some of the profits being made in the former category certainly set up a hypothesis that investment in support in providers like the London Nelson Elizabeth School of Business, IT and TikTok is not where the UMHC might expect it to be.

Oddly separate is a discussion on mental health or wellbeing strategies – previous DfE research found that “over two thirds of HEPs” (that responded to its research firm) had one. Presumably having one is a prerequisite for any decent charter mark – but either way, the group is going to help the Charlie Waller Trust to promote its CREATE toolkit (which provides guidance on the development of strategies) and the Committee of University Chairs (CUC) has committed to producing a governance framework for universities around mental health strategies and action plans.

There’s also an acknowledgement that OfS is, sort of, already regulating in this area via Access and Participation Plans – the effectiveness of that remains to be seen.

Let’s play Twister, let’s play Risk

Identification of students at risk has evolved to have three strands – the first of which is focussed on staff training. Here, a competency framework has been developed that will both set out good practice approaches to supporting students in distress, together with a minimum standard of knowledge and skills that can be expected of non-clinical staff.

The use of the word “minimum” is the interesting bit – partly because that’s in essence what a statutory duty of care would do. Hence the follow up question is – what if said minimum is not being met, and who acts if it isn’t.

The competencies are to be embedded into existing professional standards and recognition processes for key student-facing roles in higher education – and to support this process, professional bodies such as AMOSSHE, UKAT, CUBO and SEDA have been active in the development of the framework as members of the working group, as well as Advance HE, presumably from the Professional Standards Framework perspective.

I don’t want to labour the point, but again, even in less straightened times, the coverage, take up, effectiveness and so on of that approach is at least questionable – and I do get the feeling that the capacity issue and the resistance issue that seems to be out there on this agenda weakens the case for the approach even further.

I think there’s also a real question over an approach that seems to suggest that when it comes to competencies, it’s staff that matter with no reference to students. On one level the yawning gap of not talking students’ unions and their staff springs to mind – but more broadly, both from a prevention perspective and a “noticing” (or often handling) a crisis perspective, we ought to be thinking about supporting the support that students will more often than not seek from each other.

That kind of “strengthen the community” approach remains missing in much of the thinking here, but is a key feature of plenty of the equivalent strategies we’ve seen across Europe.

Data day concerns

The second bit is on analytics – the discussion focusses on technical and cultural readiness, but you’d have to assume that cost is also an issue stopping those sorts of approaches from hitting the early/late adopter phase. There’s some discussion of sector infrastructure – think HESA or UCAS or JISC – but no sense of money to back it.

The more worrying section is on information sharing between schools, colleges and providers. The intro to this section rightly says that providers can only effectively deliver proactive support and make the right adjustments to support learning from day one when they understand students’ existing needs and mental health challenges from the outset.

But while “UCAS is a well-established route for capturing mental health conditions”, all we have here is “the potential for UCAS to work with the Taskforce to consider how it might enhance the guidance for its new reference process to ensure that relevant information about applicants’ support needs is made available to providers at the earliest opportunity”, which I’m afraid does sound like some very long grass for the issue to be kicked into.

Elsewhere, there will be (another) good practice document which would guide providers in their development and adoption of case management systems, the compassionate comms work that we covered on the site a few weeks ago gets a thousand words, and the “National Review of HE Student Suicides” is to report in spring 2025 – its case reviews submission process only closed in September, partly because of an initial refusal to look at historic cases, necessitating a look at 2023/24 to allow those with weak processes to get something together quickly.

Oh – and there’s also going to be guidance on working in partnership with NHS England to encourage the development of formal and structured partnerships between providers and NHS mental health services – although oddly no mention of where they or that would fit in terms of DHSC’s ten year NHS plan and its intended three “shifts”. Maybe the relevant civil servants haven’t been talking.

We’re getting there. Where?

Take a step back, and there’s probably three ways to look at the outputs and activity so far. One would be to celebrate the progress on a set of highly complex issues in a highly complex sector. If nothing else, that three line whip on the UMHC has at least got us to “late majority” on the adoption model.

The second would be to conclude that the report itself really does set out the scale of the challenge – the difference between a ministerial tweet thread and trying to change things in the real world is usually significant, but it feels especially vast here. It’s still not especially clear that the mountain as described is possible to scale via a voluntary working group with little money pumping out frameworks and best practice PDFs.

But the third comes back to the old “could, should, must” dilemma facing any set of policymakers in a national system of regulated independent providers. Universities are, generally, better at a lot of this stuff than they were even 5 years. The question is partly the underpinning problem of me not being to prove that – not least because there’s no prospect of any measures that ask “is students’ mental health better or worse” emerging via this taskforce.

Perhaps it was inevitable that Halfon’s promise of “a set of strong, clear targets for improvements by providers…. including how the sector will publicly report on the progress measures over the coming years” was always going to be harder than it looked.

But as well as the complexities and the “is this my job” thing running up and down the chain, it’s also about the question of whether the pace of change can only ever be this slow – and if not, why a different theory of change with a different sized budget isn’t being pursued to avoid future tragedies.