Imagine you were trying, as the phrase used to go, to “get rich quick”.

You have a range of industries you could pick – so you might be on the search for one where the perceptions of quality of what you sell are fiercely argued by those who usually sell it as based on long-term outcomes, confirmed over a long period of time, long after you intend to be in the business.

You might be on the lookout for regulatory asymmetry – an industry where the quality of your outputs are only questioned once someone has been selling for a number of years, given that system picks up issues over time. Bonus points if the government seems obsessed with the culture of interaction in the main part of the industry, rather than the quality of the offer in your intended bit.

You could be looking for a sector where an unlimited number of customers aren’t only loaned the money to buy your thing, but they’re also given cash in their own account to experience your thing too. And if that industry has traditionally only sold its wares to rich people – and you intend to sell to poor people – not only will they be loaned more cash and be grateful for more cash, if the industry is under regulatory pressure to be seen to sell to more poor people, even better.

Then imagine you can find an industry with a strong brand, but where some sellers in it are struggling. If you can find a few of them prepared to allow you to sell a cut back, stripped down version of their cheapest to deliver product or service – where the cut back and the stripped down allows you to take a cut and them to take a cut – all the better.

Imagine you find a sector where merely buying the product or service can be effortlessly marketed both as highly aspirational – and as hard to access as when it was only being pushed to the posh – but you combine that with the sort of TikTok, door to door, temu.com tactics you’re more familiar with. “Live like a billionaire” indeed.

You might chance upon an industry where most of the time, customers not getting the outcomes they wanted from your thing can be blamed. You might find one where you can get an army of agents to do the selling for you. You might find an industry where nobody can see how you’re doing on those outcomes for humans, because each deal’s stats are hidden within the stats of the franchisor rather than revealed at your level.

Imagine that you then also find an industry where those you are selling to are unlikely to know what good should look like, unlikely to know their rights, unlikely to use those rights, and can be convinced they’re happy when they’re still sad, svelte when they’re still overweight, satiated when they’re starving, or educated when they’re not. Even better if it’s an industry where the product you want needs no specialist equipment, no specialist staff and can be delivered from a rented office block.

You might also be lucky enough to find an industry where the internal culture is one where people were historically never trying to profit, where people generally trusted eachother to do the right thing, behaved to keep eachother in check, and hated with a passion admitting when they got something wrong.

If you were trying to get “get rich quick”, the moral asymmetry of a rapidly growing franchised operation would be perfect – an easy thing to take advantage of, because reputational concerns allow you to coin it in, rather than cause you to rein it in.

But surely Laureate, Corinthian, Phoenix or even Trump University couldn’t happen here. Could it?

Level playing fields of dreams

There must be something coming – OfS has put an insight brief out. Subcontractual arrangements in higher education is in many ways a classic bit of dry pitch-rolling from the regulator.

We’re told that universities subcontract some of their teaching to external organisations, that not all of these organisations are registered higher education providers, and that while this can bring benefits, business models that rely heavily on subcontractual arrangements also represent increased risk:

Unless managed actively and carefully, such arrangements can negatively impact students, taxpayers, the reputation of English higher education and the university or college itself.

Well, yes. The point about the first nine paragraphs of this piece isn’t that we should assume that everyone’s at it, that all franchising is bad or even that all for-profit provision is crap. It’s that if the circumstances I describe above are true, you can be sure that someone, somewhere, will at some stage go there.

Some of the stats in the brief are eye-watering.

Since 2019-20, OfS says we have seen the number of students taught in these arrangements double – to over 138,000 in 2022-23 – now over 5 per cent of students in the sector. Looking at HESES, that’ll have grown again in 2023-24.

62 per cent of students taught under subcontracted arrangements in 2022-23 were studying business and management courses. Over time (where “time” means “a short period of time”),

…we have seen that the increase in subcontractual arrangements is being driven primarily by students taught by organisations delivering business and management courses, rather than more specialist provision.

I’d add in the remarkable rise in programmes where a foundation year is apparently necessary, or where there’s a high demand for entry-level qualifications (health and social care, construction management), or the clustering of provision in large urban areas where “introduce a friend” deals or advertising targeted at those with pre-settled status seems to both go under the radar and work a treat.

And no wonder:

A previous Insight brief on navigating financial challenges noted that entering into subcontractual arrangements as a lead provider might appear an attractive option to universities and colleges facing difficulties and wishing to generate income by growing student numbers.

Numberwang

This chart from DK represents the best data we currently have on higher education partnership. The chart is sorted by the total number of taught or registered (TorR) students – you can select a level, mode, cohort (entrants, qualifiers, and all students) and year (the latest available is 2022-23). The bars represent the number of students in each category of partnership arrangement:

- Validated – the student is taught and registered at another provider, on a course validated by the provider shown

- Registered – the student is registered at the provider shown, but taught elsewhere (subcontracted out)

- Taught – the student is registered at another provider, but taught at the provider shown (subcontracted in)

- Taught and registered – the student is both taught and registered at the provider shown

The “taught or registered population”, used for regulatory and funding purposes, is the sum of the last three of these categories. You can see, in many cases, validation activity is shown above the TorR dot.

In 2022-23 the Global Banking School (GBS) had the largest number of TorR entrants to a FT undergraduate course of any registered provider (note that there appears to be a data error, showing the total student numbers as higher than the proportion in the sole category in which GBS has students). In second place was Canterbury Christ Church University, though nearly four in five FT UG entrants registered there were not taught there.

OfS also gives us details of the characteristics of taught or registered students for each provider – you can explore everything from socio-economic background to sexual orientation, though not all categories are available for all cohorts, modes, and levels.

It has all become very big very quickly – and a glance at some of the profits being enjoyed by some of the unregistered players at least suggests that some people have indeed got very rich, very quickly.

Ker-ching

In one unregistered provider I’m looking at – a private HEI that does the bulk of its business in provision of courses franchised from universities – its latest accounts show £50m in income after its partner universities have skimmed off their franchising fee.

With those fees it then spent £18.7m on students’ education, spent £22m on administrative expenses (including sales and marketing) and delivered a £7.3m profit after tax – an almost 20 per cent profit on turnover pre-tax.

Another took in £33m in fees after franchising fees, spent £13m on education, £11m in admin expenses and generated a £4.6m profit. That’s an almost 18 per cent pre-tax profit.

A third had a £73m fees turnover with a cost of sales (ie the actual education) of £17m. With another £17m on administrative expenses, that’s £31m profit after tax – a 53 per cent profit pre-tax!

Another turned over £111m after franchising fees. It spent £50m on the education, and £42.3m on administrative expenses (inc sales and marketing) – a £28m profit.

And those are only a selection of the ones I can see. There’s plenty with more modest operations that don’t have to post full accounts, and some that are so new that it will be a long time until we can see any accounts. They might well have broken no official rules, breached no formal regulations, and be entirely legally legit. But really? Is this what it’s supposed to be all about?

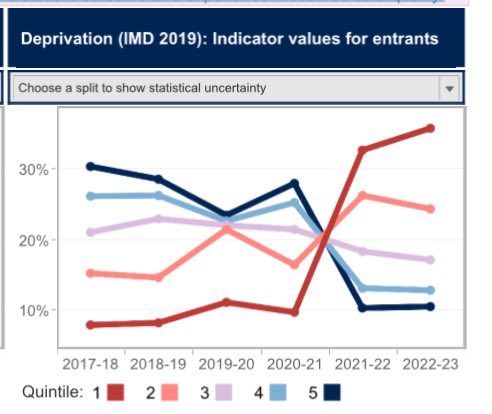

Size and shape is one thing – but you have to be quite careful with access and participation data. Here’s a provider that really has turned things around on access, for example:

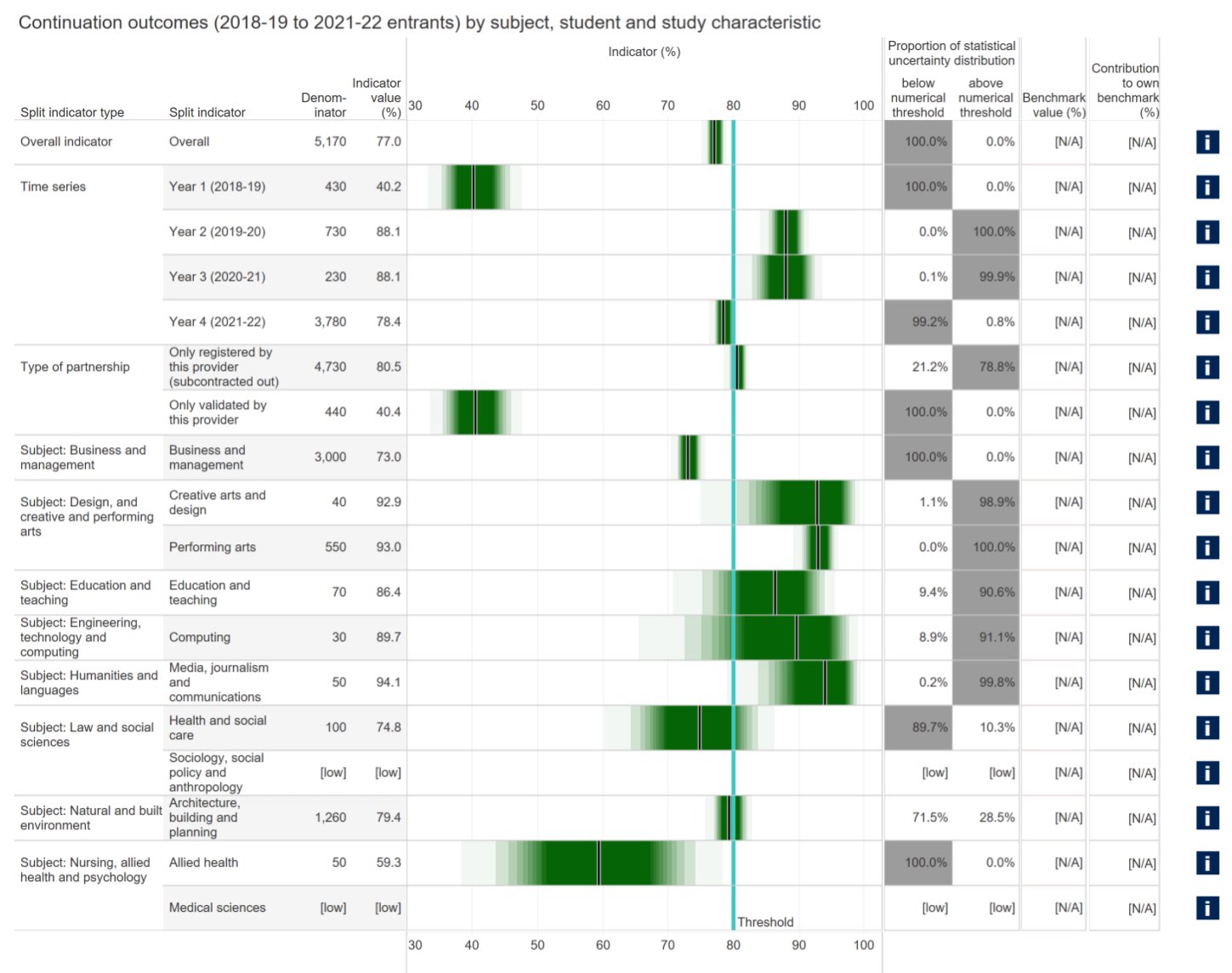

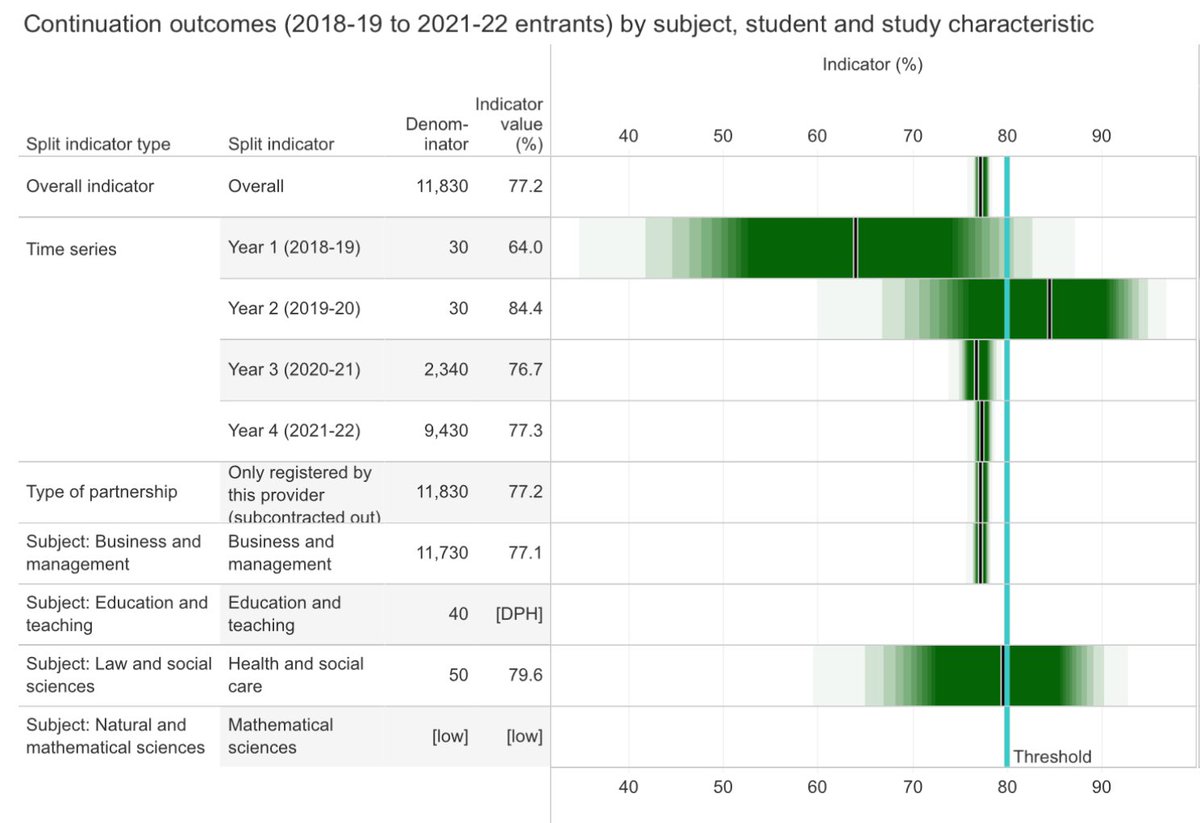

Unlike with outcomes data, you don’t get partnership splits. Here’s the same provider’s continuation data for partner college students in a context of very rapid expansion of said partners, principally offering business qualifications:

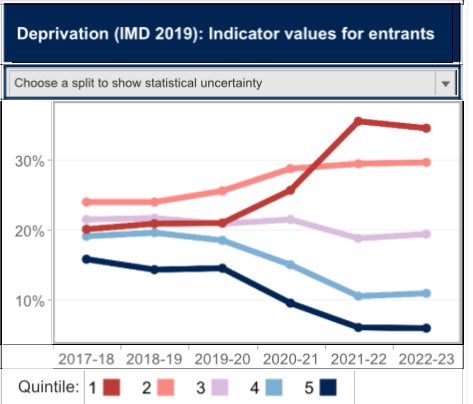

Here’s another that seems to be doing great on access:

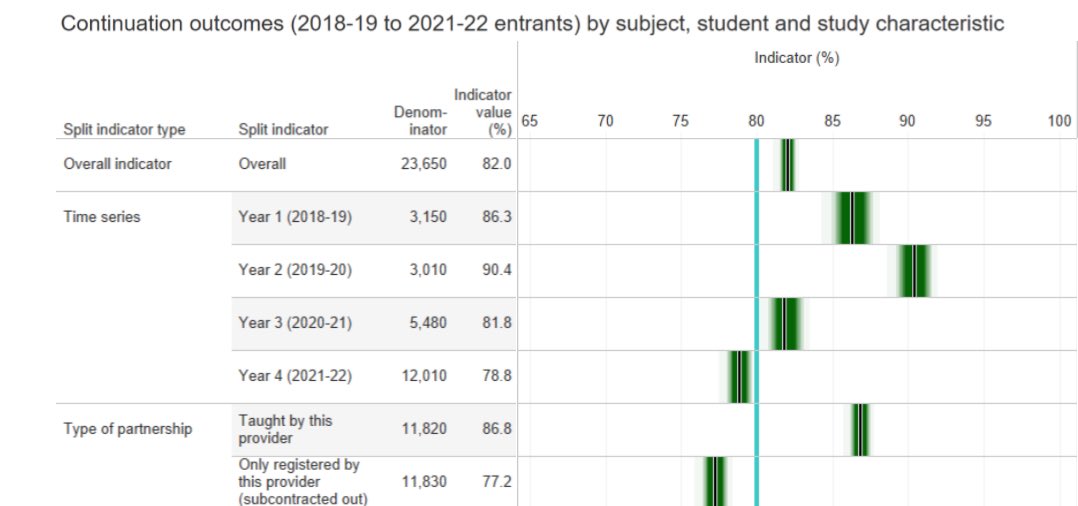

It looks like it’s down to rapid expansion. Rapidly delivering on access! Great! Oh. Here’s continuation…

And here’s just the partnership students. That is suddenly a lot of students dropping out. It’ll be a while until we see if they’re completing or progressing.

We really need to be able to see access and participation data by subject and by partner/taught splits. That’s because it’s a decent hypothesis that both at sector level and in many providers, progress on access is largely about partnerships offering business courses in private HE where the profits are high – and so is the drop out. What kind of access is that?

More broadly, you might say – well, that’s X students who are now both getting in and “continuing” that weren’t previously. But it’s also Y students knee deep in debt that aren’t. And so if even if you’re sure they needed HE, you’d have to be dead dead sure that those students wouldn’t have been better off at their local FE college.

The moral high ground

The point is that you can put all sorts of value judgements on the exponential growth seen in some providers’ partnerships – OfS’ mandarin speak demurely phrases that as:

…some lead providers [are] now teaching more students through these arrangements than directly on their own campuses. Among other potential concerns, this raises questions about the direction of travel for the lead provider’s own strategic identity, aims and objectives.

Maybe there is a little bit of keeping everyone in at lunchtime because of the antics of a small group of the naughty – OfS is more coy about the concentration of the expansion in a group of universities.

And maybe some of the egregious naughtiness is rare, or overblown. And maybe it’s OK if you’re helping the poor get educated.

But OfS’ list is, for a regulator that was in part designed to prevent this sort of stuff after scandals in the middle of the last decade, astonishing:

- Agents have recruited students to unsuitable courses, for example by misrepresenting the qualification that the course delivers, or the requirements needed to complete it successfully.

- Agents have used inappropriate methods to recruit students, for example incorrectly suggesting that the maintenance loan a student might be eligible for is a method by which the government will “pay the student to study.”

- Students have had to pay excessive charges to recruitment agents as part of the application process.

- Students with very weak English language skills have been told these are sufficient to allow them to study on a course, without the delivery partner putting in place the support to allow them to succeed.

- Students have paid agents or other third parties to falsify English language tests, to allow them to enter courses without attaining the required standard of English.

- Delivery partners have persuaded lead providers to lower entry requirements for the sake of meeting recruitment targets, often resulting in lower entry requirements for students in subcontractual arrangements than for those being taught directly by the lead provider.

- A lack of transparency for students in general about courses taught by delivery partners, where lead providers have not made it explicitly clear that the teaching has been subcontracted out.

- Students have not been clear about what constitutes academic misconduct, or the line between seeking appropriate student support and academic misconduct.

- Students have submitted assessments that are not their own work, in some cases with the complicit support of staff members.

- Staff managing partnerships at lead providers have been incentivised to prioritise recruitment and retention of students above rigorously reviewing course quality and holding the delivery partner to account.

- Lead providers have retained a significant proportion of the tuition fees for courses taught by a delivery partner, without evidence that students have been told this is happening or what these fees are being used for – raising questions about the funds available to teach and support the students on their subcontracted courses.

- Some lead providers retain between 12.5 and 30 per cent of tuition fees, with the remainder paid to the delivery partner.

Buried on Page 4 is the startling revelation that in 2022-23 and 2023-24, just over 65 per cent of students eligible and applying for SLC funding to study on subcontracted courses were from nationalities where English is not the first language (but they are resident in the UK and are not international students) – twice the proportion seen among applicants to courses delivered directly by a lead provider.

In benign charityland, that’s great – giving poor communities access to HE is amazing. Or maybe it’s a scam – milking communities already starved of social and educational capital by luring them into loans that the system subsidises. My general view is that access to HE works if the rich rub shoulders with the poor – both for the rich, and for the poor. I’m just less convinced if the poor door isn’t even on the main building – but above a betting shop 100 miles away on the outskirts of London.

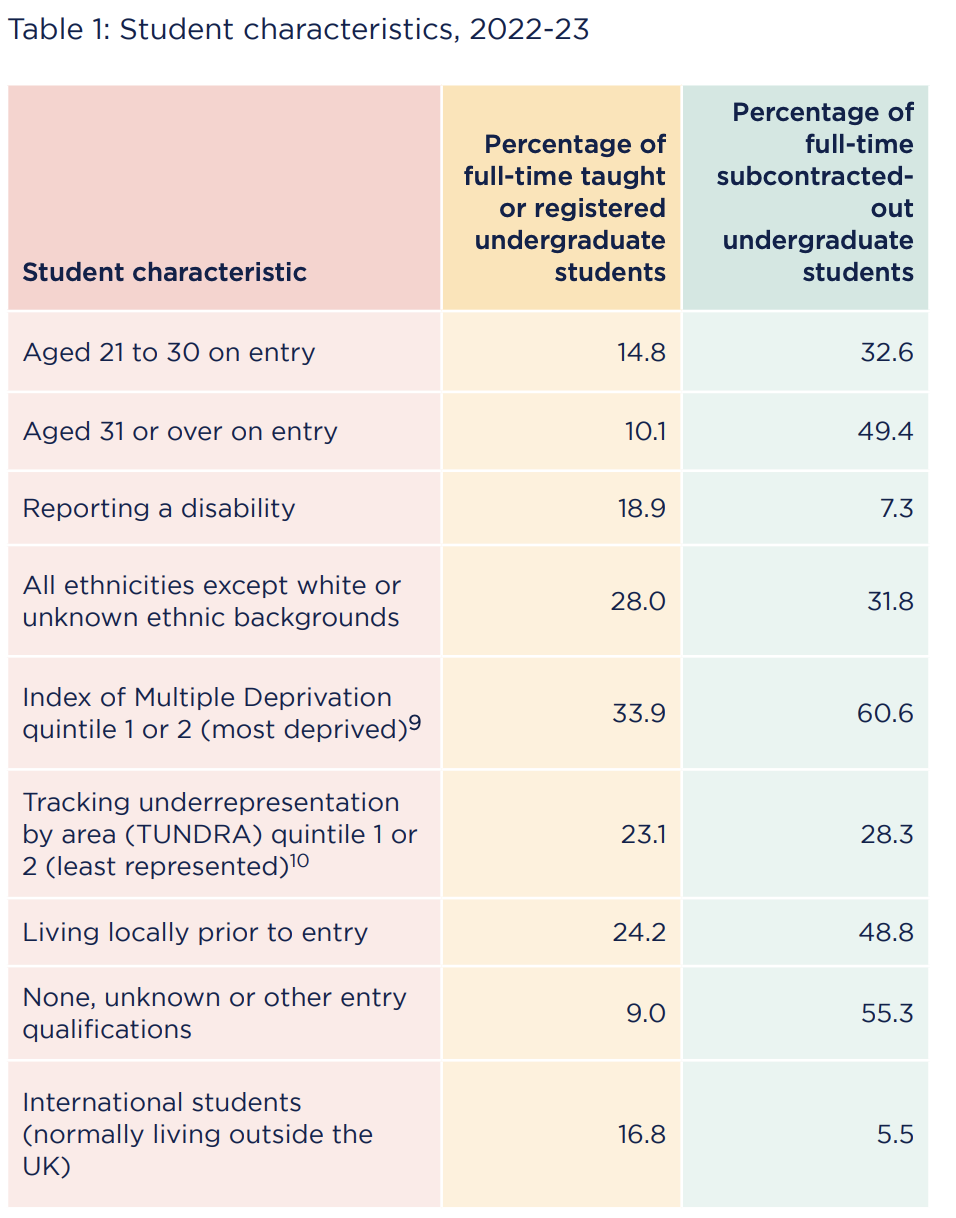

The point about those that need education the most isn’t that they don’t need it – it’s that they’re also those easiest to exploit if you were minded to. OfS says that 9 per cent of FT UGs in general have either no entry qualifications, or have entry qualifications which were unknown or “other”. But that rises to 55.3 per cent of those in subcontractual arrangements.

This table is particularly instructive. Who needs the most help from our education system? But who’s also easiest to exploit if we’re not careful?

If nothing else, for all the boasts on the impact on access, ask yourself – why are most of the intersections of disadvantage so high in that table, while “reporting a disability” is so low?

I wouldn’t start from here

One of the open questions is how we got here. When you read the OfS’ list of “examples of risks to lead providers”, you’re thinking – how on earth did this happen?

- Lead providers have investigated concerns about their delivery partners and uncovered widespread academic misconduct. This has required all students taught by the delivery partner to follow the lead provider’s academic misconduct processes, at great cost to the institution and potential detriment to genuine students.

- In some cases, there have been allegations that a delivery partner has been supporting students to cheat by supplying them with assessments, access to essay mills or contract cheating services. This has an obvious potential impact on the quality and reliability of the qualifications awarded, and the lead provider can expect regulatory action by the OfS to address this.

- Inadequate contracts have made it difficult for lead providers to terminate agreements with their delivery partners when concerns have arisen about the quality of teaching. This can result in costly or litigious exit arrangements.

- External auditors have raised significant concerns about the oversight of partnership arrangements, delaying the production of the lead provider’s financial statements and risking potential breaches of financial covenants, a loss of lender confidence and other negative impacts.

- Lead providers have prioritised the financial benefits of these arrangements over the quality of courses – for example by reducing the entry requirements for students, and so putting pressure on staff to support students to remain on unsuitable courses, and resulting in poor student outcomes and potential regulatory action.

But we know how it happens. It starts small, and gets bigger. Every decision is the least worst one that day. Nobody wants to let their superiors down. OfS has been saying you can dispense with frippery like external examiners. And the incentives. You just have to look at the incentives.

And maybe this is coming – but how is the above list not appended with examples? Fines? Public breaches of the E Conditions (Governance and Management). Why aren’t students applying to those providers, right now, in the possession of knowledge that would help them avoid the above places?

OfS’ solution is as you would expect it to be. It’s included a checklist to assist lead providers’ governance and oversight of subcontractual arrangements.

- It asks governing bodies to consider if it has expertise at a senior level to manage the increased risk associated with this business model, including the challenges of commercial dealings with a delivery partner.

- It poses the question – are there clear and recorded delegations in place relating to the instigation of new subcontractual partnerships?

- It suggests a probe – are there clear and recorded arrangements to identify and manage conflicts of interest relating to partnership arrangements?

- It nudges other questions – has due diligence been done on the potential subcontractual partnership, does it include a review of how the tuition fees passed to the delivery partner will be used to support the student experience, does it include a review of the delivery partner’s financial sustainability, and are there clear, comprehensive, written contractual arrangements between the lead provider and delivery partner.

Amazingly, that checklist even points out that:

…the priorities of delivery partners, especially commercial organisations, may well differ from those of the lead provider. The latter should ensure that its senior team and board have access to skills in the areas of commercial practice, risk, internal control and audit.

But maybe, just maybe, that’s the actual problem.

Gouda cheese and a brioche bun

In 2017 when the Higher Education and Research Act was being piloted through Parliament by Jo Johnson, in some ways the legislation was late – the sector had bodged together a regulatory regime from an era with number controls and low fees.

The “cashpoint colleges” scandals of the middle of the decade pointed specifically at the need to “never again” that problem. But there were, as always, other incentives around.

On 9 September 2015, at Universities UK Conference no less, Johnson delivered what became a signal for those designing the subsequent legislation and regulatory regime, and anyone who might have been considering exploiting it:

Many of you validate degree courses at alternative providers. Many choose not to do so. I know some validation relationships work well, but the requirement for new providers to seek out a suitable validating body from amongst the pool of incumbents is quite frankly anti-competitive. It’s akin to Byron Burger having to ask permission of McDonald’s to open up a new restaurant. It stifles competition, innovation and student choice, which is why we will consult on alternative options for new providers if they do not want to go down the current validation route.

What that Byron burgers argument never saw coming wasn’t artisan upstarts selling fancy cheese and brioche buns to the middle classes, or even to the working classes. It was that the relaxed regulatory regime to cause it may well have ushered in the odd Dyson university or an innovative NMITE, but alongside it a whole host of unregistered providers selling franchised cookie-cutter business and management foundation year-attached degrees to the easiest to exploit to buy them.

As I said above – it’s not that we should assume that everyone’s at it, that all franchising is bad or even that all for-profit provision is crap. It’s that if the incentives and the regime allow it, you can be sure that someone, somewhere, will at some stage do it.

And it’s why, ultimately, OfS’ well-meaning efforts at causing governing bodies to ask better questions, or deploying its boots on the ground interrogation teams to providers whose outcomes it still hasn’t published at unregistered provider level, just won’t do.

Risk-based regulation

Because really, this is all about risk. If it’s the case – and the insight brief suggests it is – that the chosen methodology to cause innovation in provision has also ushered in a range of crystallised risks so severe that the NAO is involved and OfS has had to admit have happened on its watch, you end up with choices.

You could double down on design – up the inspections, publish the outcomes, ask governing bodies to toughen up and somehow persuade internal cultures to be less needy of the money and less worried about access when you’re piling on the pressure in the other direction.

You could propose (and get sign off on) restraints – no expansion in higher education is meaningfully possible at these rates, everyone should be on the register for your “fit and proper person” tests, or maybe you insist on seeing the contracts. The pitch rolling at least suggests that some or all of these could be coming.

But you’d still have little to offer on aspiring to be better. You’d still be swimming in a sea where the choosers have no power. You’d still be stuck with measuring outcomes over time. The legacy part of the sector would still be underfunded. And every rule you put in will be found a way around by those who want to – and apparently can – get rich quick. Even if some got out, you’d have thousands of students left high and dry – often hundreds of miles from the provider whose Student Protection Plan offers nothing of the sort.

You could insist – nostalgically – on controls on numbers such that those without a track record that one necessarily needs to judge over time are prevented from expanding until that judgement can be made. You could cause what’s genuinely there in unmet demand for local adult provision to flow into FE Colleges that need the throughput. Like we, sort of, used to.

Or you could just fess up to your new ministers and admit it. You tried your best – but the strategy was wrong. Perhaps – as is evident in multiple European countries – innovation and quality and cost control can be driven by other things, other ideas, other fundamental frameworks than competition. Maybe a single “playing field” for everything from UCL to Bungleton Brideshead School of Business isn’t really possible.

Maybe some of the decent, high quality, well-meaning, modest profit private provision will go or contract if the government changes tack. But maybe affording some the ability to make vast private profits quick out of the provision of non-specialist higher education via long-term loans to the poor is just not worth the risk.