Ahead of the budget, Keir Starmer has announced that the cap on bus fares in England is to rise to £3 in England in January.

Back in 2023 a cap of £2 for single trips was introduced on most bus routes as a cost of living initiative—initially for three months, and then extended until the end of this year.

When it was introduced, it was one of the few cost of living initiatives that had students in mind—at the time, Buses Minister Richard Holden said:

We’re investing £60 million to cap single bus fares at £2 to help families, students and commuters and help get people back on the bus.

It is a cap that many, particularly students, have come to rely on.

Cost of learning

I don’t need to remind readers of the cost of living pressures students are acutely experiencing and have been doing for several years now. Students are often devoid of any government support beyond a home student maintenance loan that is poorly means tested and whose maximum has failed to keep pace with inflation.

As a result, students have been facing trickier decisions in balancing their studies, navigating the cost of living crisis and experiencing a time deficit with a greater need to do part time work made at a cost of participation and the wider university experience.

To students who are commuting, and for those who live further and further away from campus, this announcement will be a cause of stress and put more pressure on an already strained wallet. Many will be doing rough calculations for next term like these:

| Contact hours across 3 days a week | Contact hours across 5 days a week | |

| Current plan: £2 cap (£4 a day) | £132 | £220 |

| January plan: £3 cap (£6 a day) | £198 | £330 |

These calculations are based on an 11 teaching week term for students who would get a bus under the current and new plans without any discounts or additional bus passes.

For students in London or Greater Manchester, fares will remain capped at £1.75 and £2 respectively, due to transport policy being devolved.

Those who are lucky enough to have scheduled contact hours across three days instead of five will be £66 poorer. For students with greater contact hours with scheduled sessions across 5 days, perhaps on placement, will be £110 down on current arrangements. These aren’t small amounts of money and this increase in travel costs will likely lead to a decline in student engagement.

Five years ago, the cost of transport would be accounted for as part of students’ finances, the same as their weekly food shop and maybe a coffee with their course mates. Now, price increases add further strain onto students who are experiencing a cost of living crisis that few recognise still as a crisis – including students themselves.

If a student already needs to balance part time work alongside their studies or is choosing whether to attend one lecture a day, the £6 may no longer be worth it if they can watch a recorded version after a work shift. For students on placement, if they are in receipt of any bursaries or support with transport costs, it is unlikely to increase alongside bus prices.

What’s next?

At the weekend, the Sunday Times reported that analysis commissioned by the Department for Transport has concluded the £2 limit is not financially sustainable for the taxpayer and bus operators, having cost £200 million in its first ten months alone, between January and October 2023.

The study is said to have found that every £1 spent to support the cap generated just 71p to 90p of economic and social benefits. It has not (yet) emerged to accompany the announcement.

What we do know from the National Travel Survey (NTS) is that two-thirds (64%) of trips for those in managerial and professional occupations are made where private transport is the main mode in the trip—people who have never worked, long-term unemployed and students make the highest proportion of trips using public transport.

The Department for Transport press release says that “moving forward”, the government will also explore more targeted options that deliver value for money to the taxpayer to ensure affordable bus travel is always available for the groups who need it the most—“such as young people”.

In Scotland, an NUS study found that 42 per cent of students use public transport to get to their place of study, but for many, the cost of fares are debilitating. Its Young Scot National Entitlement Card provides free bus travel for under 22s – over 55 per cent of students, approximately 311,000, are aged 22 or over, and therefore are ineligible for free bus travel.

NUS Scotland’s Cost of Survival survey found that 21 per cent of students had missed class and a further 7 per cent had missed placement because of the cost of public transport, and NUS UK’s Move It survey found that the cost of travel had impacted 32 per cent of students’ ability to eat a meal.

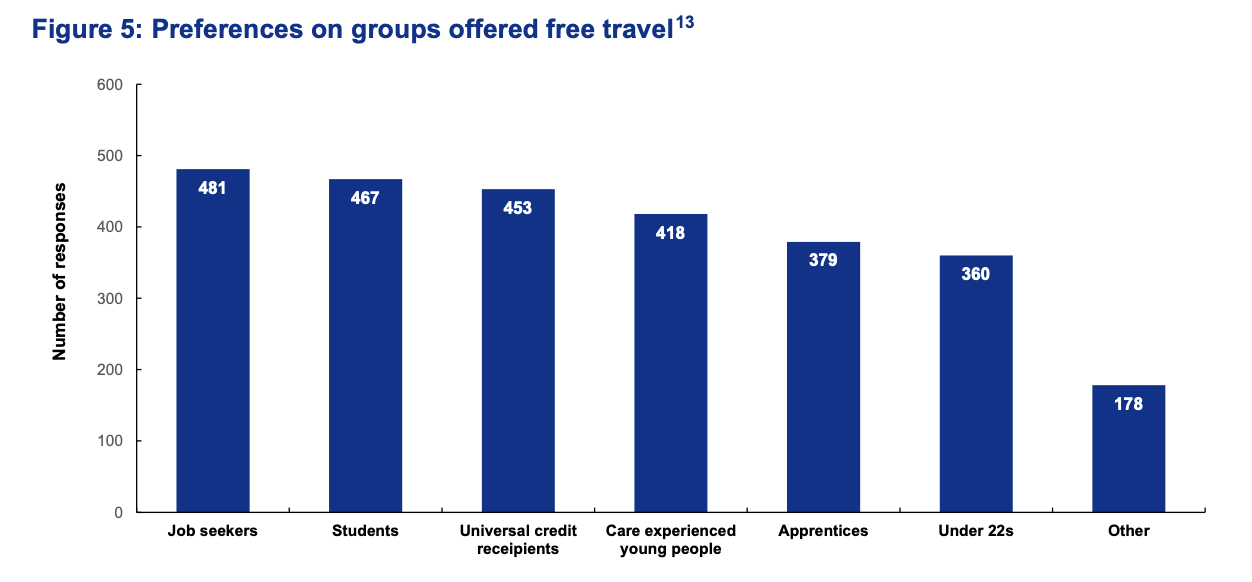

This report from KPMG for the Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT) examined policy options that might be used to support a sustainable transition away from a £2 fare cap. A national survey asked the public to consider groups potentially eligible for free travel under a more targeted scheme. Students came second:

The DfT release reminds us that a Buses Bill, to be introduced later this parliamentary session, will give local authorities the power to deliver “modern and integrated” bus networks that “put passengers at the heart of local decision making”.

It also says it will “bring an end to the current postcode lottery” – which manifests as rip-off term passes for some students and poor route coverage for others.

The cost to government of the current English National Concessionary Travel Scheme is approximately £700 million annually. This provides 8.7 million bus passes and 567 million journeys—rounding that up to £1bn could extend eligibility to the 1.4 million people receiving Universal Credit who are searching for work and the 2.5 million students at higher education institutions in England.

If not, that Buses Bill can and should mandate some kind of concession for students—as is the case across the continent. It’s an infinitely better bet than increasing their debt to cover getting to campus.