The Home Office’s quarterly immigration stats are out, along with ONS net migration figures – and the narrative war over who should take the credit and blame for a 20 per cent fall in net migration to 906,000 is playing out in the usual way.

Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch said her party had failed on migration:

We got this wrong. I more than understand the public anger on this issue, I share it.

Suella Braverman, former home secretary, claimed credit for the drop in net migration, saying it:

…is a result of the changes I fought for and introduced in May 2023. That’s when we started to turn the tide.”

Former Conservative home secretary James Cleverly also claimed credit:

Today’s migration figures are the first to show the impact of the changes that I brought in as home secretary… we see the first significant downward trend in years. Changes that Labour opposed and haven’t fully implemented.

We might expect all of that from the last government – but a party spokesperson for Labour said the latest migration figures showed the government had started the “hard graft” of tackling the issue, and was “cleaning up the Conservatives’ mess”.

We’re pretty much in a rats-in-a-sack political monoculture fighting to take credit for getting numbers down and blame where they’re from. But what’s caused the decrease so far? Guess.

ONS director Mary Gregory’s central quote is that the fall in the latest year was:

…driven by declining numbers of dependants on study visas coming from outside the EU.

But how has that impacted main visa holder numbers?

Down but still up

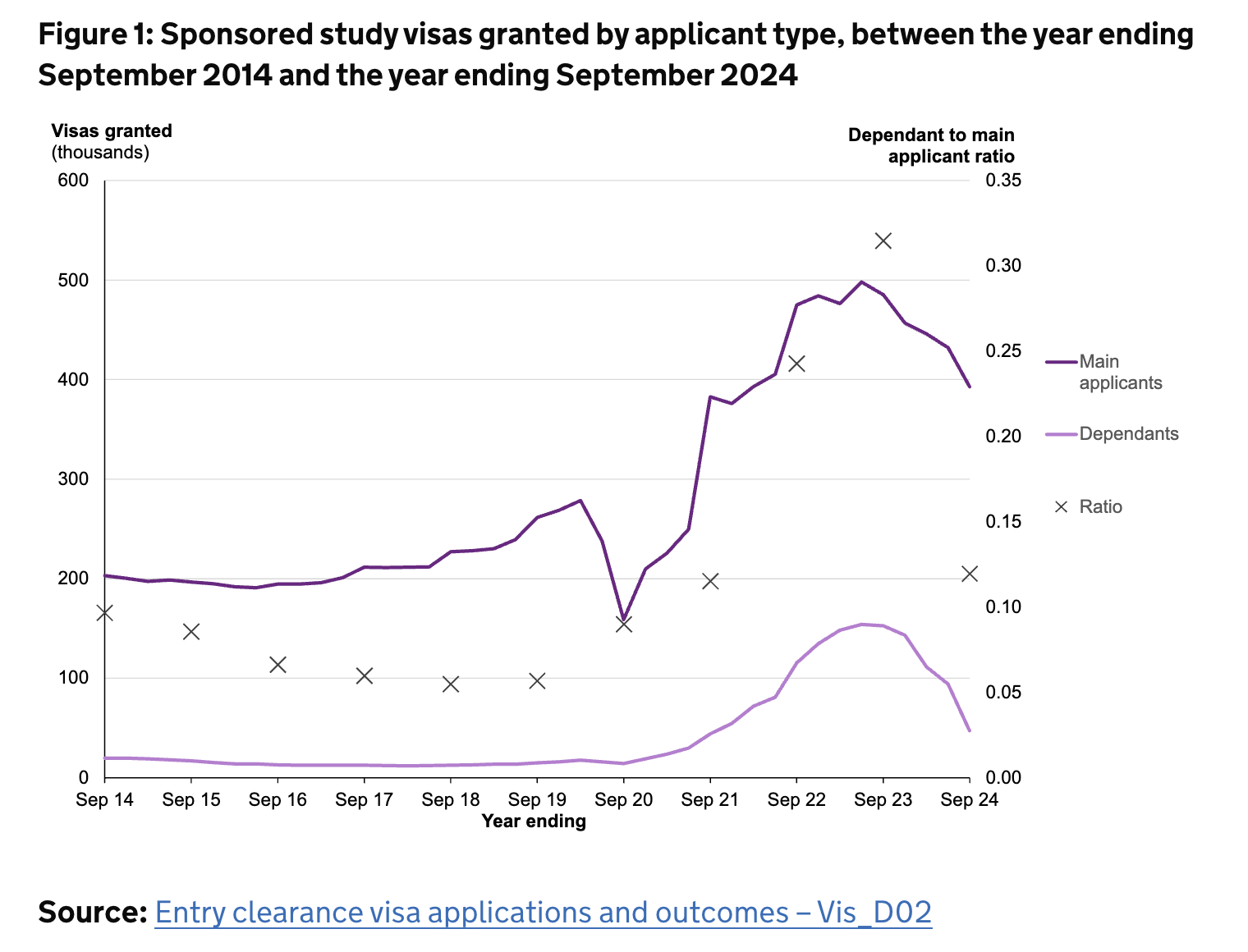

In the year ending September 2024, there were 392,969 sponsored study visas granted to main applicants – 19 per cent fewer than in the year ending September 2023, “but 46 per cent higher than 2019”. Do you see what they did there?

The Home Office narrative on the causes of the rise and fall is fascinating. The increase, readers are told, was down in part to travel opportunities re-emerging as COVID-19 related restrictions were eased – along with changes to the immigration system following the UK’s departure from the EU which ended free movement for many EEA nationals.

The headline collapse? It notes that in the year ending September 2024 there were 46,961 visas issued to student dependants, 69 per cent fewer than the previous year but almost 3 times higher than in 2019.

So take some emigration, and add in some falls in immigration of both main visa holders and dependants, and that’s that 300k (ish) that the last government was promising.

The drop, of course, followed a policy change for courses starting on or after 1 January 2024, whereby only PGRs are allowed to bring dependants (partners and children) to the UK. In the first 9 months following this change (January to September 2024) the number of sponsored study dependent visas granted fell by 84 per cent compared to the same period in 2023, from 114,293 to 17,978.

The Home Office says that the restrictions “may also have partly impacted” the number of main applicant visas granted, which decreased by 16 per cent over the same period.

Outta control

You might be thinking “well no s*it Sherlock”, but one of the things I find fascinating about that is the way the narrative plays into the ministerial agenda and the need for the Home Office to look like it’s in control.

As ever, we’re not told in this release how many (either then or now) students brought dependants – as I noted here, in 2021/22, 81 per cent of PG students brought 0 dependants. That’s your 19 per cent collapse right there.

This is the country comparison chart, showing that most of the increase in students between 2019 and 2023 was from India and Nigeria, and that both have fallen in the latest year (by 31 per cent and 62 per cent respectively).

The delayed publication of the impact assessment of the dependant changes had a “central estimate” of a 25 per cent fall in PGT visas. It also said that when it looked, 77 per cent of students from India brought no dependants, with Nigeria on 38 per cent. If you said to yourself “the numbers of those without dependants ought to have remained constant”, that should have meant a 23 per cent drop from India.

In other words, the headline drop has broadly been where the Home Office thought it would be – but the impact has been very different from country to country.

If we isolate PGT visa grants in Q3 and do a year-on-year comparison, the biggest percentage falls were from India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Ghana, Sri Lanka, Iran and Afghanistan. Everyone else dropped by less than 20 per cent – and some richer countries even saw big (at least in percentage terms) gains – Kuwait, Italy, Germany and the United States.

So maybe something else is going on. If you think about the value of the Rupee and the Naira in 2019, imagine that tuition fees for a PGT course have increased by, say £5k to £20k since 2019. Then add in UK inflation on cost of living, and increases in visa fees (including graduate route and the NHS charge).

The difference in that scenario is a 55.48% increase in real terms costs from India, and a 219.75% one for those from Nigeria. And in terms of numbers rather than percentages, the other big three falls (other than China) were Pakistan, Bangladesh and Ghana – and all three have seen purchasing power in the UK decline over the past few years too.

Even if the dependant ban was reversed, it’s not clear it would make much difference – other than plunging international students even further into poverty on arrival. The era of depending on the disposable income of the global south to prop up UK HE may be coming to end not because of quality, or reputation, or even morality – but because of money.

Refusals

A quick look at refusal rates – which vary hugely between countries. It’s not an exact science, this, but if we look at decision outcomes for Q3 2024 amongst the 20 biggest countries for applications, refusals vary between under 0.5 per cent for Taiwan, South Korea, China, Germany, Malaysia, Hong Kong, France, Kuwait and Canada, up at 5 per cent ish for Pakistan, Nigeria and Nepal, and over 10 per cent for Bangladesh.

We don’t know if that’s increased scrutiny of some countries on suspicion of fraud, or more actual fraud, or poor application practice – but it does seem to be something particularly impacting Global South countries.

Do they stay or do they go

It’s always interesting in this release to look at what’s happening with staying – not least because the simplistic call on international students is to “take them out of net migration stats” on the assumption that they behave like tourists.

Of course a decent chunk of the PGT increase has been about the graduate route – and a total of 159,218 extensions into the graduate route were granted to main applicants in the year ending September 2024, some 52 per cent higher than the previous year (104,501), reflecting a consistent annual growth since the route’s introduction in July 2021.

Indian nationals represented the largest group of students granted leave to remain on the route (72,570), representing almost half (46 per cent) of the total in the latest year.

That tells us that increasingly we need to think about not just the number of students on one year PGT visas, but the number of students here for three years and how that temporarily grows the population.

You might still argue “well, OK, they leave after the graduate route”, at which point we turn to the ONS stats.

It says that long-term net migration of non-EU+ international migrants who initially arrived in the UK on a study-related visa decreased to 262,000 for year ending June 2024 compared with its (updated) YE June 2023 estimates of 326,000.

That is partly about leaving – emigration of non-EU+ migrants who initially arrived on a study-related visa increased from 51,000 in YE June 2022 to 113,000 in YE June 2024 – that includes those who emigrated but had transitioned onto a different visa type during their time in the UK.

But more non-EU+ students and their dependants have been staying longer, and nearly 1 in 2 transitioned to a different visa type after three years from YE June 2021 – an increase from 1 in 10 after three years from YE June 2019.

This ONS chart shows the total number of non-EU+ nationals who initially immigrated long-term into the UK on a study-related visa by flow type, for year ending (YE) June 2019 to YE June 2024:

Here’s another way to put it:

Again, some of the change is about the introduction of the graduate route – the point about that if you’re concerned about net migration being that even if folk leave afterwards, you end up adding to the population substantially.

They don’t like the remainers

Here’s all visa transitions for those who arrived in the UK on a study-related visa in years ending (YE) June 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023 cohorts, between YE June 2020 and YE June 2024 – including the graduate route:

Clearly, a higher proportion of non-EU+ nationals who initially arrived in the UK on study-related visas transitioned onto work-related visas in more recent years. But do they then leave?

Crucially, a much higher proportion of those arriving on a study-related visa in YE June 2021 transitioned to a work-related visa after three years in the country (38 per cent) compared with just 11 per cent who transitioned to other visa types.

That, says ONS, is a large increase compared with YE June 2019 arrivals, where 7 per cent transitioned to work-related visas and only 3 per cent transitioned to other visa types.

So more arrive on a study-related visa, and they transition to work visas at higher rates than earlier cohorts. ONS notes that analysis from The Migration Observatory suggests the reason a higher number of students transitioned onto different work visas at the end of their studies is because of the decision to make care workers eligible for the Skilled worker (including Health and Care) Route in early 2022:

More than half of all people who transitioned directly from study visas to skilled worker visas in YE June 2023 went into care work. It is possible that restrictions on work visas may have some effect on these patterns, though this is hard to predict. The proposed policy changes do not significantly affect eligibility for main applicants on the care visa, but would prevent people with children or partners from using the care route to stay in the UK after their studies.

We’re also given some fascinating geographical impacts. Using the latest published data available from HESA, ONS says that in the academic year 2018 to 2019, London, Yorkshire and the Humber, and the North East had 25 per cent or more of new higher education students who were previously resident in a non-EU country. By 2022 to 2023, this proportion had increased above 25 per cent in all areas of the UK and was above 40 per cent in the East of England, London, Scotland and the North East.

In other words, sharp falls in numbers have geographical, regional impacts – presumably economically as well as socially.

What’s next

I think it’s fair to say that the prospects of there being further immigration changes are slim – the political consensus is nowhere near supporting it. If there’s a lesson for the sector and/or DfE, it’s that the expansion was simply too fast for the politics, let alone the infrastructure – and now it’s the economy (,stupid) of the countries the UK recruits from that looks like the biggest influence on future numbers.

Further changes then become dependent upon the extent to which Labour can escape the doom loop of having to pull blunt levers – which disproportionately impact higher education – to get headline numbers down. Immigration policy is tightening across the West – Canada, Australia and large parts of Europe are all caught up in a lagged and complex data picture versus a kneejerk anti-immigration right, as is much of Europe.

But unlike those countries, what’s almost exclusively missing from the UK debate is any acceptance that immigration – both high and low-skilled – might be required in the medium term to keep an economy with an ageing population going.

UK HE could get in behind calling for sense – but the reality is that UK HE “offers” high-skilled. The “Deliveroo visa” allegation is one way to frame it – another is that in some ways, the UK might have been using its reputation to plunder what wealth is there in the Global South to bankroll British kids’ HE, luring those with dreams on the promise of careers and businesses only to have them end up funnelled into the low-skilled jobs that Brits don’t seem to want to do and that we can no longer get those from Eastern Europe to do.

A UK HE system that learns to live with fewer, better skilled, higher-earning international PGTs from the Global South just feels like a better and less exploitative bet.